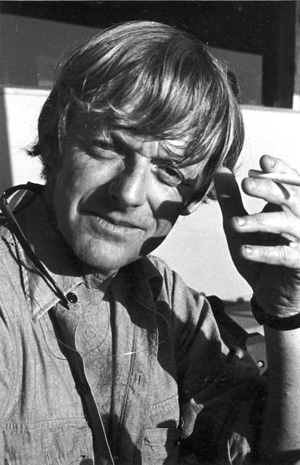

Photo by Louise King

Michael Dormer was born in Hollywood, California in 1935 into a family of writers and musicians. At an age when most children are learning to walk, Dormer was already drawing. Recognizing his talent, Dormer's parents enrolled him in a small sculpture and ceramics school in Del Mar, California when he was five years old. Louis Geddes, a popular artist during that period, encouraged the child and helped him develop his artistic talents.

Dormer won his first national art award at age twelve; a first prize in a National Fire Prevention poster contest. At fifteen, Dormer became more interested in music than in art. He wrote, arranged, and played guitar with an experimental jazz quintet. This association lasted slightly more than two years. At age eighteen, Dormer resumed his involvement with art and refined his draftsmanship by hiring out his services as a freelance illustrator and cartoonist for a number of national men's magazines ranging from Esquire to girlie magazines. Concurrently, he worked and expanded his artistic capabilities as a political cartoonist for a San Diego newspaper, the Independent (published weekly from 1902 to 1970). Dormer was nearing twenty when he went on the road, financing his expeditions around the United States by painting barroom murals and playing piano in saloons.

Dormer moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1950s and, after a brief, scholarship-financed stint at the Chouinard Art Institute, co-founded an off-beat novelty product business featuring his cartoons. The company did well for several years and the products were successfully marketed nationally, but eventually business slowed and he abandoned it for greener pastures in San Francisco, a place considered more artistically enlightened.

Rubbing elbows during the turbulent 1950s with socially and politically active, "try anything" creative giants like Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, David Meltzer, and Jack Kerouac, stimulated the young artist into a flurry of productive activity. He painted and sold his first serious works there. In 1957 he moved south to La Jolla, California and set up a painting studio, augmenting his income by becoming a part-time night club comic and jazz poet. During this time he published an innovative art and poetry magazine, Scavenger, and co-founded an art gallery in Lee Teacher's coffeehouse (The Pour House) in Bird Rock that featured early works by avant garde artists of the time, including John Baldessari, Fred Holle, Peter Matosian, Donald Borthwick, and the late Guy Williams.

In the early 1960s, Dormer moved east with his new bride to Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He won several awards in local painting competitions and exhibited and sold his paintings at the Kenmore Gallery in Philadelphia. A publishing contract in New York enabled Dormer to write and illustrate a half-dozen humor books. After a year-and-a-half, Dormer's marriage dissolved and he moved back to California.

In the spring of 1964, Dormer and the woman who was to become his second wife, Florence ("Flicka") Oglebay, toured Europe on a working vacation. Visiting the great galleries and museums was an aesthetic eye-opener for the young artist. Culturally saturated, the couple returned to California. Dormer immediately left for Mexico to repeat the process.

In the mid-1960s, Dormer settled in Ocean Beach, a beach community in San Diego, where Oglebay lived with her sister. The artist's writing and drawing talents were marketable in Hollywood, so Dormer began commuting there to work in the motion picture, radio, and television business.

In 1963, Mike Dormer and Lee Teacher built a six foot, 400 pound concrete statue out of cement, iron, a mop, a light bulb, and a beer can. They dubbed their creation "Hot Curl". The statue mysteriously appeared on the rocks over Windnsea beach in La Jolla, holding a beer in one hand while gazing out over the ocean in search of the perfect wave. Hot Curl soon became a star, appearing in several scenes of Muscle Beach Party (1964), a cult classic starring Frankie Avalon, Annette Funicello, Buddy Hackett, Don Rickles, and Morey Amsterdam, among others, and featuring the first film appearance of "Little" Stevie Wonder. A Dormer mural provides the background for the opening credits.

In 1967 Dormer created and co-launched Shrimpenstein, a raucous and wildly irreverent children's television show which aired live weekdays on Channel 9 in Los Angeles. Shrimpenstein, which remains a cult favorite to this day, was hosted by the late Gene Moss as Dr. Von Schtick and featured aminiature Frankenstein monster (a wacky ventriloquist dummy that was "created" when jellybeans were thrown into the monster machine). This top-rated show ran for a year and was allegedly one of the favorite programs of Frank Sinatra's legendary Rat Pack. Shrimpenstein also had a huge following among college students all over Southern California. Contractual disputes brought an untimely demise to the venture and Dormer returned to San Diego to rest and reevaluate. During the ensuing three years, Dormer stopped painting. It may have been a case of "burnout", artistic reassessment, or something else. Dormer attributes part of it to the Pop Art movement that was sweeping the United States and for which he had little enthusiasm. During that time, he concentrated on magazine illustrations, cartooning, and feature work. In 1970 he resumed his work with "aluminum paintings" (paintings executed on aluminum foil), a complex process with which he had experimented in the late 1950s with the encouragement of the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA).

The Dormers returned to Europe in 1972 and settled in Venice, Italy. Flicka (Dormer had married her in 1967), worked with an Italian scientific group on an early storm warning system designed to protect the battered city from rampaging winter storms off the Adriatic Sea and Dormer acted as historical researcher for the team. The celebrated and controversial poet Ezra Pound and art collector Peggy Guggenheim were their neighbors, although Dormer never spoke to Pound because the poet was living in penitential silence. Dormer's frequent breakfast companion in his pensione was the renowned architect Louis Kahn, designer of the Salk Institute in La Jolla and other landmark structures. "I thought this affable little guy was just someone who taught architecture at the local college until one of his students finally clued me in", Dormer reminisces.

Dormer also became involved in early holographic photography experiments conducted in Venice with the goal of recording for posterity the city's rapidly disintegrating art works using this new three- dimensional imaging technology. Back in the United States once more, Dormer broke into the travel writing business in the mid-to-late 1970s and his humorously written and colorfully illustrated articles appeared regularly in San Diego Magazine. Many of these pieces were reproduced and incorporated in the advertising brochures of hotels and services in the areas he visited. Dormer's first illustration for San Diego Magazine was created in 1954 and, over the past fifty years, hundreds more have appeared on its pages.

As the 20th Century wound down, Dormer began to concentrate less on commercial art and more on fine art. Recently, when asked to sum up the last fifty-plus years of his professional life, he volunteered the following statement:

"I've reached a point in my life where I'm feeling calm and integrated. I was a restless guy in the past and always felt as if I were being pulled in a lot of different directions. There were many creative things that I wanted to do and I succeeded in doing most of them pretty well. It took a lot of energy. Sometimes I was doing four things at once... painting, writing, cartooning, music, frantically traveling around and just plain looking at things. At this stage, experimenting in painting looks like the way I'm going to spend the rest of my life.

Professional artists are very hard workers. There's an attitude among people who don't make art that we have it made ... sitting around in our comfy houses all day, fiddling around with a blob of clay, paper, paint, and brushes. They're dead wrong. We work with all of our senses. Art takes great concentration, touch, coordination, timing, imagination really "seeing" things, and a very esoteric sense of mathematics. You've got to have discipline and compulsion to do it right. What I do is invention. It is all experiment because I, myself, am an experiment. Whether I am a successful experiment or not is strictly up to future historians."